Celia, A Slave

Research Paper About the Book

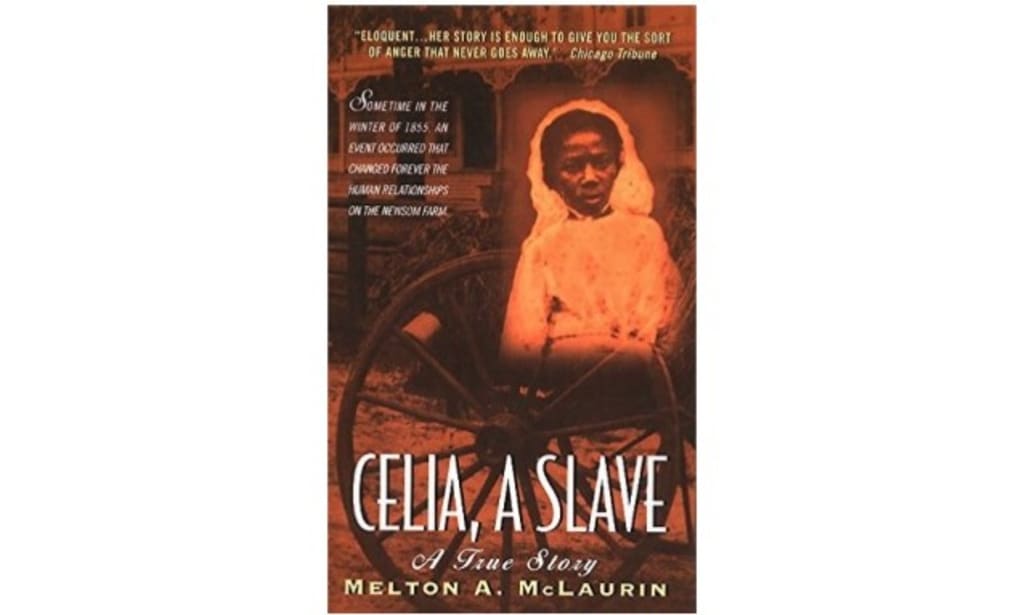

Celia, A Slave was a book published by Melton A. McLaurin based on a true story about a woman named Celia. Celia was an African American female who lived in Audrain County, Missouri, which bordered Callaway to the North, until she was purchased by Robert Newsom in 1850 (McLaurin, 11). By this year, she was approximately fourteen years old, but other than that not much was known about her before her arrival to the Newsom farm. Historians do not know if she was born in Audrain County, whether she had been the property of a farmer, or how many masters she had had previously (McLaurin, 11). While working on the Newsom farm, Celia cooked for the Newsom household, which consisted of Robert Newsom, his son Harry, and his daughters, Virginia and Mary (McLaurin, 11). In addition to her household duties, Robert Newsom treated her as his concubine. Newsom molested and raped Celia, which eventually led to his murder. The relationships of race, gender, and power in the antebellum South were revealed in many aspects of Celia’s life as a slave, as shown in her experiences with rape by Robert Newsom and her court case.

For many female slaves, such as Celia, rape was an ongoing threat to their well-being and often a reality, which in Celia’s case resulted in the murder of her master, Robert Newsom. As stated previously, Newsom repeatedly raped Celia for five years, beginning at the age of fourteen (McLaurin, 28). Then, some time before 1855, Celia became romantically involved with George, another of Newsom’s slaves (McLaurin, 29). During this time, Newsom regularly visited Celia in her cabin and made sexual demands of her. Not too much long afterwards, George gave her an ultimatum that Celia break off her relationship with Newsom or he would have nothing to do with her (McLaurin, 30). Because of his ultimatum, Celia was placed “in a quandary that exemplified perfectly the vulnerability of female slaves to sexual exploitation by males within the owner’s household” (McLaurin, 30).

Celia asked for help but was forced to take matters into her own hands. Celia appealed to Newsom’s daughters, Virginia and Mary, for help by mentioning her pregnancy and being sick. However, she did not mention her relationship with George (McLaurin, 31). Despite Celia’s efforts to stop Newsom’s sexual advances, he continued to have sexual relations with her, so on June 23, 1855, she confronted him (McLaurin, 33). She begged him to leave her alone and yet, “Newsom brushed aside her request and, as if to emphasize his right to have sex with her, informed Celia that ‘he was coming to her cabin that night’” McLaurin, 33-34). Therefore, she threatened to hurt him if he made any more sexual demands of her and acquired a large stick (McLaurin, 34). On the night of Saturday, June 23, Newsom came to the cabin where Celia was residing with the intention of having sexual intercourse with her, but instead she refused (McLaurin, 34-35). When she did so he advanced towards her, so she grabbed the large stick and struck him in the head. She then hit him again, afraid that he would harm her, and with that second blow he died and fell to the floor. Not knowing what to do and fearing for her life, she panicked and burned Newsom’s body in the fireplace (McLaurin, 35-36).

In the antebellum South, white men and some white females commonly viewed black women as sensual and promiscuous. In contrast, white women were seen as moral and pure, but also ‘… belonged within families and households under the governance and protection of their men’” (Qtd. McLaurin, 117). The law only protected white women from sexual assault and did not grant those same rights to female slaves. Also, white women were not allies to female slaves. “Anger and resentment was a characteristic response of white women in slaveholding households when faced with the possibility of a relationship between a male in the household and a female slave” (McLaurin, 26). Essentially these women were powerless in preventing such acts from happening and consequently, they vented their anger upon the slaves. Celia experienced one of the two forms of responses, anger, from Newsom’s daughters (McLaurin, 26).

White male slaveholders sexually exploited their female slaves, with molestation and rape. According to woman scholars, “… as many as one in five female slaves experienced sexual exploitation” (McLaurin, 116). The slaveowners were even knowledgeable about the prevalent sexual abuse that female slaves had experienced (McLaurin, 24). For instance, “recent scholarship has shown that there sometimes existed a willingness on the part of fathers and sons to share slave mistresses” (McLaurin, 27). Around the same time Celia was brought to the Newsom farm, a very well-known southerner by the name of Senator James Henry Hammond had a sexual relationship with two slaves that were mother and daughter. Then later, he gave the women to his legitimate son, Harry (McLaurin, 27). The fact that this father and son shared these two women was an illustration of how white men viewed black slaves as property, rather than human beings.

The events of Celia’s life demonstrate the previously stated trend of sexual exploitation. Male slaves rarely faced this same kind of abuse. It was more common for them to face “a dilemma imposed by [their] own sense of masculinity and [their] inability to alter the behavior of their master” when the ones they love were being sexually abused by the man who owned them both (McLaurin, 29-30). “Slave narratives, by both men and women, were filled with references to sexual demands placed upon female slaves” (McLaurin, 116). Celia was intentionally purchased to be abused. Additionally, it “is certain that Newsom’s reasons for acquiring Celia were different from those that motivated his previous slave purchases (McLaurin, 21). He intentionally chose to buy a young female slave as a replacement for his wife who had been dead for nearly a year. He wanted a sexual partner and Celia would soon fulfill this role (McLaurin, 21). When Newsom was returning to Callaway County, he “raped Celia, and by that act at once established and defined the nature of the relationship between the master and his newly acquired slave” (McLaurin, 24). The sexual nature of their relationship would never change because it was as if Newsom felt entitled to use her for his sexual pleasure whenever he pleased even if she refused, because she was a woman and a slave.

Celia was treated differently because of her situation. She soon gave birth to two children, both of which may have been Newsom’s children. McLaurin stated, “Because of her relationship to him, Newsom rewarded Celia with material goods beyond those which could ordinarily be expected by a slave” (McLaurin, 28). For example, he gave Celia her own cabin, which was more luxurious compared to the housing that majority of the slaves resided in. The cabin, however, may not have been considered rewarding to Celia because it was used as a place that Newsom would visit regularly to engage in sexual intercourse with her. Furthermore, when Celia tested her master’s power, “it was unacceptable because gender mattered in both the social conventions and in the laws that upheld slavery” (138). A slave being empowered and defying their master’s power would have threatened the institution of slavery.

Celia’s court trial revealed the imbalance of power in the antebellum South. Throughout the antebellum South, the law did not recognize the rape of black women, and “in Missouri, sexual assault on a slave woman by white males was considered trespass, not rape, and an owner could hardly be charged with trespassing upon his own property” (McLaurin, 110-111). So, common law practically condoned sexual assault of female slaves because it did not protect them against rape, and white slaveholders were able to get away with rape without being charged for their crime. “Black female slaves were essentially powerless in a slave society, unable to legally protect themselves from the physical assaults of either white or black males” (McLaurin, 113). Therefore, white male slaveowners dominated female slaves and were not charged for raping them, while a black slave could be charged for committing the same crime, and if they assaulted a white woman, they would be executed. For instance, “Celia’s relationship with Robert Newsom provides a compelling, if hardly unique, example of the power of the white patriarch” (McLaurin, 137). Not only were female slaves sexually vulnerable by the power of slaveholding men, they were regarded as property rather than humans to be used for whatever purpose their owner may have wanted.

According to McLaurin, “Finally, because race and gender are issues with which … society continues to grapple, and because both remain factors in the distribution of power within modern society, the case of Celia, a slave, reminds [people] that the personal and the political are never totally separate entities” (McLaurin, xiv). For example, Celia’s court case demonstrated how one’s race and gender can greatly impact the verdict of that individual’s trial. In Celia’s case, the jurors found her to be guilty for the murder of Robert Newsom, and she was sentenced to be hanged. Judge William Augustus Hall, a man born in Portland, Maine with unknown views about slavery, presided over Celia’s trial (McLaurin, 80). However, he removed all grounds for a plea of self-defense because Celia’s attorney “… had been unable to obtain direct testimony from Celia about a perceived threat upon her life, for under Missouri law, as was the case in most southern states, a slave could not testify against a white person, even one deceased” (McLaurin, 106). Because the judge refused to allow any reference to the threatening nature of Newsom, the defense was at a disadvantage since self-defense was their only legal argument. The personal obstacles Celia faced were the obstacles any slave women in her position would have encountered.

In conclusion, Celia’s court case provided significant insights into how gender and racial persecution resulted in enslaved women feeling especially disempowered in cases where protecting themselves from sexual exploitation was needed. Not only was Celia purchased to be raped, she never had any help from the slave community or white women in the household, such as Newsom’s daughters. When she defended herself physically, the verdict was a forgone conclusion because white slaveholders had all the power while black female slaves had little to none. As McLaurin stated, “Although the slaves’ humanity could never be completely denied, it had to be minimized for the institution of slavery to function” (McLaurin, 118).

About the Creator

Jade Rosario

My name is Jade Rosario. I’m 22 years old, and I love to write stories.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.